Emerging Markets: Consumer Markets of the Future

A thematic primer on FMCG and the rise of the emerging-market consumer

Executive Summary

Everyone has an emerging markets story to sell: Asia, rising middle classes, consumption. The problem is most of those stories assume straight lines and ignore how bad policy, bad incentives and bad capital allocation can wreck good demographics. We should also not forget about geopolitical tensions and conflicts.

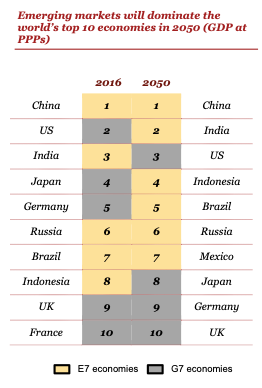

Overall, the data still say one thing quite clearly: the centre of gravity of global GDP and consumption is drifting toward today’s “emerging” world. PwC projects that by 2050, six of the seven largest economies (PPP) will be emerging markets; China, India and Indonesia sit in the top four, and the E7 economies together dwarf the G7. Asia as a whole is on track for roughly half of global GDP and ~40% of global consumption by 2040.

FMCG has been a laggard and an unloved sector for years. Probably because companies like Procter & Gamble have not yet figured out how to build a datacenter or design the latest chips. Starting from high valuation multiples (paying 30x earnings for a company growing 3%YoY is rarely a great idea), higher real rates, and cost inflation have taken multiples and sentiment down. But the winning FMCG companies of tomorrow are likely the leaders of today. They have strong brands, pricing power, distribution networks and an established presence on the shelf and in the consumer’s mind.

While growth across the FMCG sector will not be spectacular, emerging markets offer attractive opportunities. And ageing populations in developed markets still consume for longer.

The Big Picture: Gravity Is Moving

PwC’s World in 2050 model is built on demographics and productivity:

The world economy can more than double in size by 2050 (real, PPP).

The E7 (China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Russia, Mexico, Turkey) grows to almost half of global GDP; the G7 drifts to roughly a quarter.

China and India together become larger than the US and EU combined on PPP terms.

When the model was built there was no talk about AI. I think the model may look a bit different today, but the direction is similar.

You don’t need exact percentages to see the point. By 2040 Asia alone could represent roughly 50% of global GDP and 40% of global consumption.

Demographics

Demographics don’t tell us where stock prices will be next year. They do tell us where the customers are likely to be over 20–30 years.

Young where it matters

PwC and UN data show:

The G7 working-age population shrinks materially out to 2050.

Countries like India, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Nigeria and Pakistan still have rising working-age cohorts.

Even EMs age fast from a low base. Old-age dependency ratios climb, but they stay structurally younger than the G7.

So the world for the next decades looks roughly like this: a lot of older people in rich countries, and a lot of younger and middle-aged people in emerging markets that are gradually moving closer to rich-country income levels.

But coming back to the consumer:

Those older cohorts do not stop consuming. They may change what they consume (more health, personal care, home care, probably less alcohol or sugar depending on personal preference…). As long as the population ages without shrinking too fast this is acceptable for me as an investor.

Those younger EM cohorts move up the ladder from basics to branded to premium across categories: food, beverages, personal care. They become more like developed market consumers.

People consume longer

Life expectancy is higher in almost every region than it was for the last generation, and it may be even higher in the future. That means more years of consuming everyday products.

So we have two simultaneous facts:

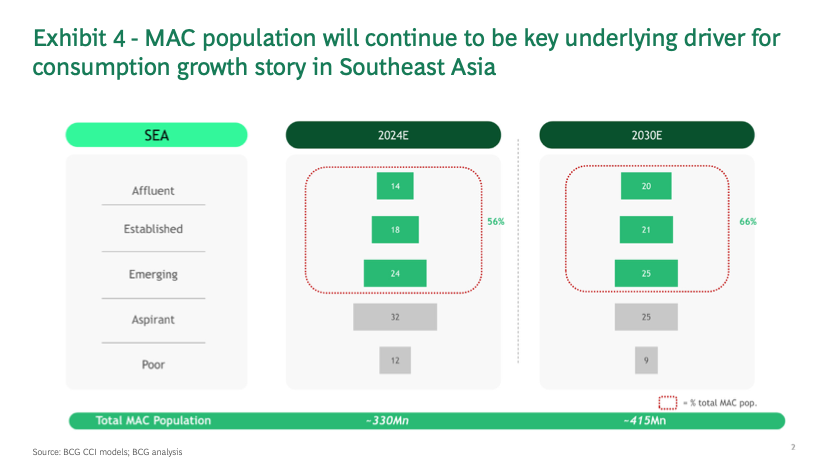

EM and ASEAN add hundreds of millions of new consumers to the branded economy (about 140 million in ASEAN alone).

Ageing stretches the period over which people consume basic FMCG products in developed countries often with higher spend on health, wellness and personal care.

From an FMCG perspective, this is a long-duration demand story: more consumers, consuming for longer, with room for premiumisation in many categories.

What the EM Consumer Actually Buys

Consumption happens in S-curves. Early in life and at low income levels, you focus on necessities. As incomes rise, spending accelerates and broadens across categories. Later in life, consumption tends to level off again. That pattern is driven by both age and income. There is only so much toothpaste you can use per day, no matter how much you earn. Let’s take this across categories with some examples:

Food: from loose staples and street food → packaged staples, branded noodles, sauces, snacks → higher protein and dairy, better quality and safety.

Beverages: from water and tea at home → branded soft drinks and RTD coffee → functional, low/no sugar, “better for me” drinks.

Home & personal care: from basic soap and generic washing powder → specialized detergents, shampoos, deodorants → skin care, baby care, colour cosmetics, fragrance.

In ASEAN specifically, BCG’s “Next Chapter” piece sketches the demand engine clearly:

A MAC (Middle-class and Affluent Consumer) population of about 330m today grows to about ~415m within a decade.

A “twin-engine” pattern where lower MAC trades up cautiously and upper MAC behaves more like developed-market consumers in health, sustainability and brand preferences.

Heavy use of digital channels, social commerce and “shoppertainment” as part of the shopping journey.

The sectors I care about are the ones that sit right in the middle of these shifts and get touched multiple times a day and also multiple times across various consumer cohorts: food, beverages, home care, oral care, personal care and everyday beauty.

FMCG: A Defensive Sector That Can Still Hurt You

FMCG has a great marketing deck for investors. We see non-discretionary categories, strong brands with pricing power, resilience in recessions, healthy balance sheets and increasing dividend streams. None of those protects you from overpaying, or from owning the wrong businesses in the sector.

The recent fall of alcohol-related stocks is a clear lesson: when consumption projections shift it has massive effects on the whole investment case. Most investors talk about “staples” as if they’re all the same. They are not. There is a narrow group of compounding machines and a long tail of mediocre assets. It is no coincidence that companies like Nestlé or Unilever were already among the largest food companies in the 1990s and still dominate today. That persistence tells you something about the economics and moats in this space.

The staples sector has had quite a bad run over the last few years. There were inputs cost spikes, squeezed margins, FX-related earnings misses, private label competition. The consumer is trading down. Also coming from high valuations after a decade of very low interest rates there were some re-ratings in the sector. This combination of fundamentally resilient businesses with weaker recent share-price performance and less fashionable narratives is exactly what made me have another look at individual names. Structurally and in the long term, I think the sector remains attractive, but only for the right companies at the right price.

What I Want to Own for Decades

Tom Russo has spent decades owning global consumer brands through every kind of disruption. His framework resonates strongly with me, and I recommend watching a few of his interviews on WealthTrack or listening to recent podcasts with him. Keeping in mind Russo’s principles at The Tiny Family Office I want to own businesses in the FMCG sector with a few important characteristics:

Indispensable products

Products that are used daily and are hard to cut even in stress: staples, basic beverages, oral care, household cleaning, basic beauty and skincare.

No optional luxuries (I own LVMH - but that is a different story)

Businesses that have already proven they can survive

Businesses that have already operated for decades in difficult environments like South Africa, Indonesia, Brazil, India, China

They know how to work around tariffs, wage spikes, FX restrictions, random taxes.

Aligned stewards & globally leading position

Either family control or owner-like management

Willingness to spend heavily on capex, brands and distribution during bad times

Sometimes size matters: in many categories the leading FMCG companies today are likely to still be among the leaders in 20–30 years.

The Bear Case: When the Theme Does Not Work

The bear case is not that demographics will change quickly or that GDP projections are completely wrong. The bear case is that companies fail to capture the consumer. This may happen for many reasons:

failure to capture digital shifts and consumer preferences (e.g. shoppertainment on TikTok)

local and regional brands gaining market share (we may see some uprising Asian staples giants with global reach in the future)

political shifts including price controls, windfall profit taxes, tariffs or other restrictions along with FX risks

management mistakes, M&A at peak multiples, endless restructuring (when restructuring costs become a yearly part of your financial statements as it happens in industries like Airlines then something is not right), SBC and compensation packages that incentivize short-sighted behavior.

These are only a few, but very real, reasons why the EM consumer theme might disappoint at the stock level, even if the macro story plays out.

The Tiny Family Office and EM Exposure

So how do I translate all this into something I can hold for decades and sleep well at night?

Treat EM consumption as a structural tailwind, not a short-term catalyst.

We’re talking 2040–2050.

A small number of high-conviction positions.

Stay within the circle of boring products.

Food, beverages, home care, oral care, basic beauty.

Respect price.

Even the best businesses will disappoint if you pay 30–40x for low single-digit real growth.

The beauty of an unloved sector is: you often get windows where the market throws the baby out with the bathwater. Those are the moments I care about.

If the long-run projections are roughly right, the large global FMCG players should do just fine – probably even from current valuation levels, provided I stay selective and disciplined on price.

In one of the next TTFO notes, I’ll put more numbers behind this theme with an investment case on a leading FMCG company and a very simple back-of-the-envelope 10-year IRR.