We’ve entered a world where debt is no longer a problem to be solved, but a condition to be managed. Across the developed world, governments have quietly accepted that deficits are permanent and reform is politically impossible.

They will not pay their debts back in real terms, instead they will inflate them away.

For two decades, every crisis, whether financial, a pandemic or geopolitical, was met with the same response: more spending, larger central-bank balance sheets, more promises.

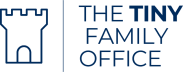

The result is simple arithmetic: the global sovereign-debt stock now exceeds $100 trillion, roughly equal to world GDP. What began as an emergency measure has become a structural habit.

In the Eurozone, deficits remain entrenched even during growth phases as seen in Figure 2 below. The United States behaves no differently.

The political cost of austerity is too high, and the electoral cycle too short. True reforms that would reduce deficits require pain and long-term thinking. These are two things modern democracies have systematically unlearned. This is even clearer for countries where there are more than two politically relevant parties. If really needed, reforms could be passed in the United States and the UK, much more so than in Germany, France or Italy where any party rarely has more than 25% of the votes.

Europe’s structural trap

The continent faces zero real growth, negative demographics, and rising fiscal commitments. Europe does not have the economic firepower of the United States, especially lagging in growing sectors like technology.

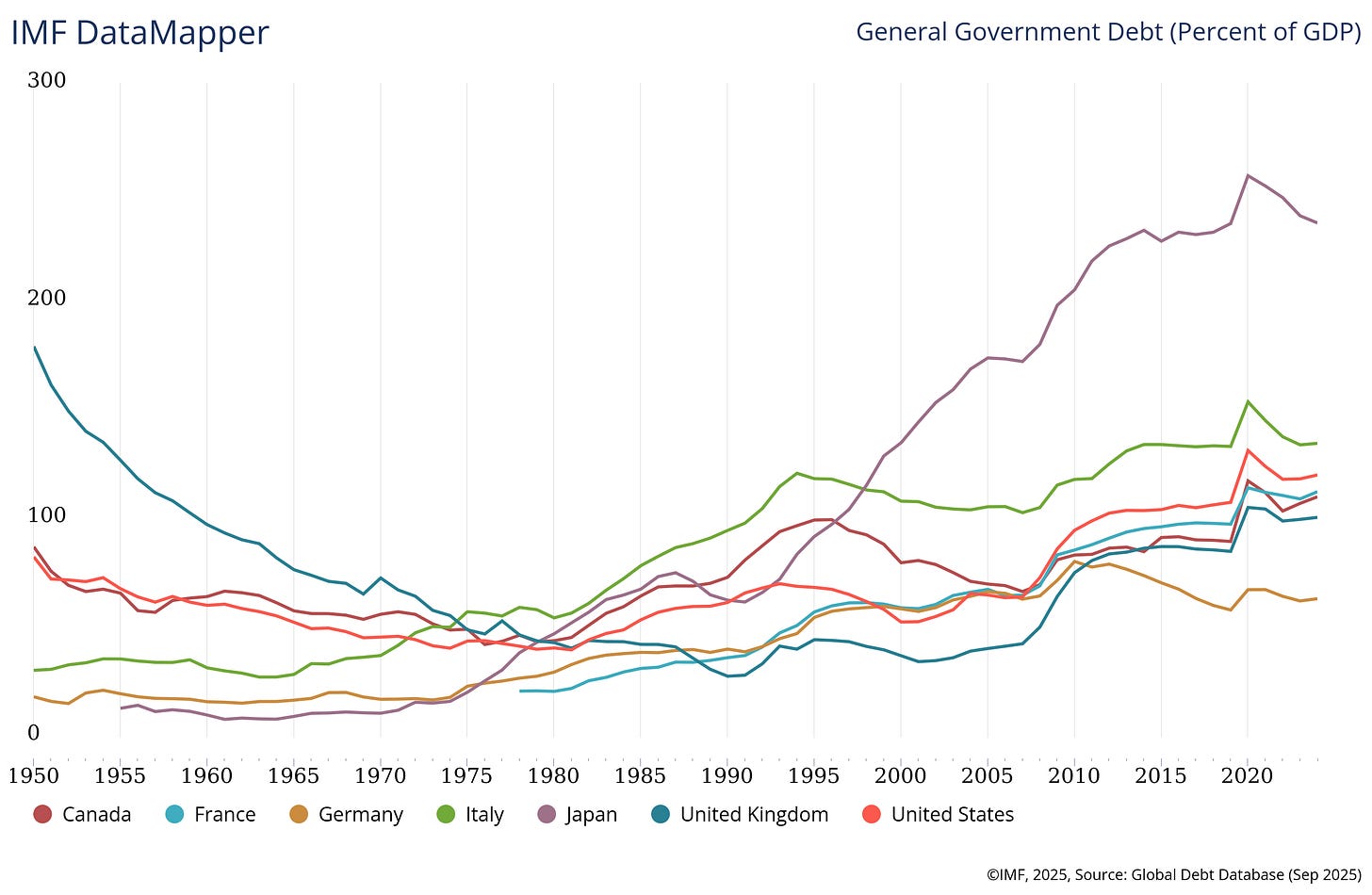

Social systems built for expanding populations are being supported by shrinking workforces. Take Germany’s pay-as-you-go pension system: contributions from a worker are literally transferred to a pensioner the next week. Benefits are indexed to wage growth, even as the contributor base shrinks. With an aging population, this system simply cannot function when one worker must finance not one but two dependents.

Europe’s true problem isn’t just debt. It’s demography.

The working-age population in Germany and Italy is already shrinking. Productivity cannot offset the demographic drag, and an aging electorate votes for transfers, not competitiveness.

By 2050, the age-dependency ratio in developed Europe will explode. China is hit worst, followed by Japan, Italy, Germany, and France each moving from roughly 55 % to near 80 %. The U.S. faces a more favorable, although not perfect, outlook, helped by immigration and more flexible labor markets. It also lacks a rigid pension system like Germany’s. For all major economies worldwide the trend is the same: upwards.

Central banks: lenders of last resort

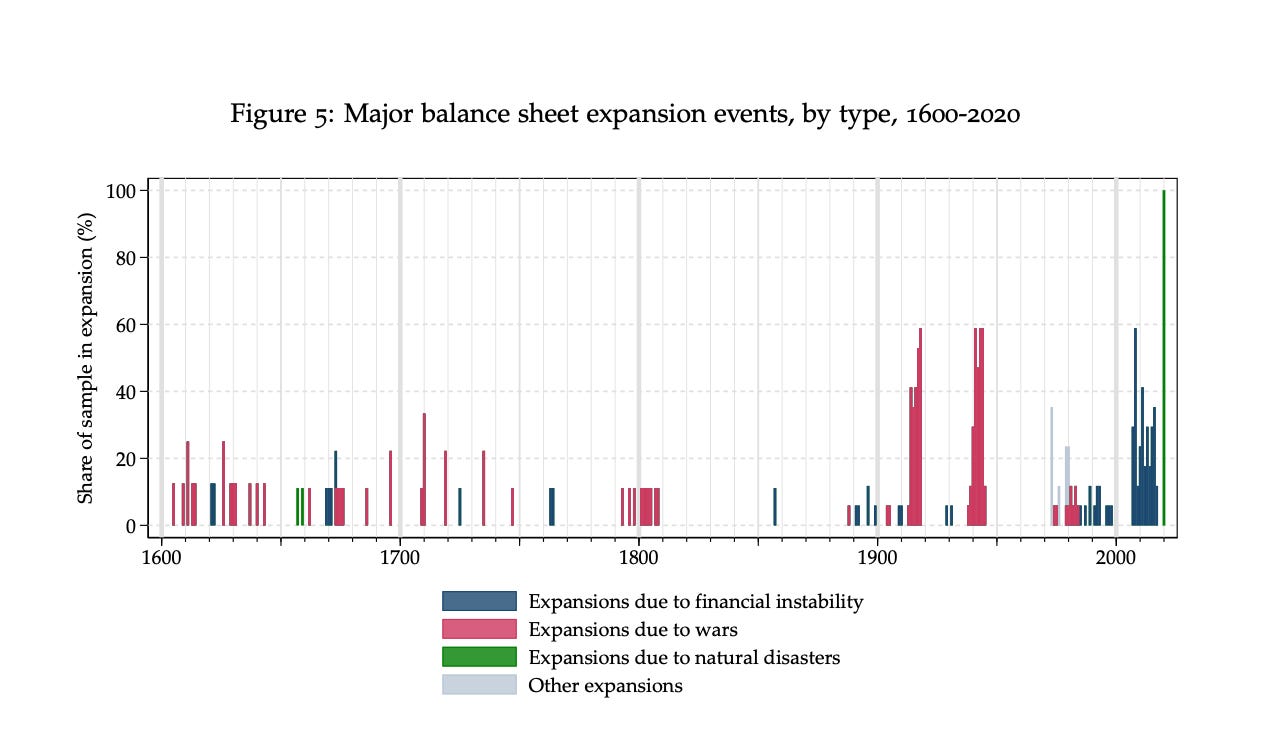

The current debate about “unsustainable” debt levels forgets an essential truth: we have been here before.

As Schularick and his co-authors recently documented in “The Safety Net: Central Bank Balance Sheets and Financial Crises, 1587-2020”, central banks have acted as lenders of last resort for over 400 years.

From wars 300 years ago, to the Great Depression, and from 2008 to COVID-19, the pattern is the same as balance sheets expand, crises stabilize, and (at least in our century) capitalism survives.

Liquidity creation is the mechanism by which the system prevents collapse.

Every time the central bank balance sheet grows, financial fragility rises, but the world continues to turn.

Moral hazard increases, but so does stability. But moral hazard is not only something that applies to the financial industry - banks, shadow banking or private credit. It also has an impact on society as a whole. It shapes how we view and tolerate risk. What is the definition of risk if there is no consequence?

If I know that in a crisis the government will backing me anyway, then where is the point in maintaining financial sanity? Why not spend freely, have no savings, buy real estate at any prices, or take margin loans to invest in equities? The same applies to social security: If the government bails out companies, and supports households at any cost, why shouldn’t I demand my share? Why work hard if I can rely on government benefits?

This is certainly no moral compass that a society should want.

I am therefore not particularly worried about the existence of public debt itself.

The bond market will, at times, demand its price; nominal yields may rise; volatility will return. But as long as major economies borrow in their own currencies and their institutions remain credible, systemic collapse is not the base case.

The risk is not financial, it is political.

Inflation: the slow default

Inflation remains the politically elegant way to erode debt.

It’s the “slow default” a gradual transfer from savers to debtors that stabilizes the macro system while destroying purchasing power. It is, in effect, a stealth tax on those who hold nominal assets: deposits, pensions, and life-insurance policies.

Inflation alone will not help reduce debt or make it more serviceable if economic growth lags. This is a recipe for disaster. A shrinking economy combined with rising inflation is therefore not just an economic issue; it is a social one.

Because the majority of the population in Europe holds cash savings, not equities or property, inflation acts as an attack on middle-class wealth.

That asymmetry between the capital-owning minority and the cash-holding majority fuels political resentment. One could also argue it may fuel a generational conflict between the young work force and the dependents over time.

Capitalism

And this is where my real concern lies: not with debt levels or market volatility, but with the erosion of faith in capitalism itself. If fewer and fewer people profit from the system, if the younger population feels locked out of ownership and upward mobility then they will vote accordingly.

We no longer live under monarchies that could suppress dissent; we live in democracies where discontent expresses itself through elections.

If economic frustration deepens, voters will turn left, and so will policymakers. That means more rent controls, wealth taxes, and “excess-profit” levies. We may see all kinds of reckless policies.

Not immediately, but inevitably, as generational turnover accelerates and the median voter’s wealth position declines.

It is not only a matter of equality, of the haves and the have-nots. It is a matter of chances. If my income is crippled by exorbitant taxes to fund failing social security systems, if my employer moves career prospects abroad, if my wages stagnate: Where is my perspective? If I am young I may vote for parties that promise to take from those who have more. This risk is far smaller in the U.S. (Republicans often think Democrats are “the left,” but they have little idea how left Europe can actually be). The comparison doesn’t hold.

Old voters will dominate electorates for some time, blocking reforms and, depending on their ideology, perhaps offsetting the younger generation’s redistributive tendencies. But that is temporary. Once faith in capitalism is lost, it is almost impossible to restore, and that loss leaves scars on generations.

This is the real long-term tail risk for investors.

What this means for us as investors

For investors, the implications are clear.

The system can handle the debt most likely. Especially if debt is used to invest in the the future of a country and generate economic growth. There may be volatility in the bond market at some point. In the long-run a broken system cannot handle the political consequences. Therefore, the focus should shift from balance-sheet sustainability to political sustainability.

Government deficits ultimately flow into corporate revenues, whether that is through social systems, infrastructure, healthcare, or defense spending.

If inflation and financial repression are the long-term equilibrium, companies with pricing power, tangible assets, and recurring cash flows will outperform. Equities are the natural beneficiaries, even if higher nominal yields persist, companies will adapt.

Long-duration government bonds and fixed-income products are the ultimate losers in an inflationary equilibrium, unless governments find creative ways to force institutions and private investors to hold duration. I generally do not hold bond exposure in my portfolio, but on a family-level we have some exposure to medium-term government bonds. If rates move higher the hit will be tolerable, and nominal yields will reset over time.

Capital should be invested in jurisdictions where the social contract still favors enterprise over redistribution. For me that is still the U.S. and Europe, but it is something to monitors closely. I would not want to own companies heavily dependent on physical assets in Germany or France, for instance, where policy risk is rising, and prefer firms flexible enough to shift operations abroad if needed.

Conclusion

Debt will not kill the system. Politics might.

Public debt has become a permanent feature of advanced economies.

Central banks have learned to manage it, but capitalism requires legitimacy, and trust.

If too few people feel they benefit from it, they will vote to change the rules of the game.

For investors, the challenge is not to fear government debt, it is to anticipate the policy responses born out of inequality and resentment.

Those who hold scarce, productive assets will always be able to adapt. Those who hold nominal promises will fund the transition.

The art of living with debt is understanding that the next default may not be financial.